No edit summary |

|||

| Line 146: | Line 146: | ||

During the filming of ''Star Wars'', Cushing was provided with a pair of boots far too small to accommodate the actor's size twelve feet. This caused a great deal of pain for him during shooting sessions, but the costume designers did not have enough time to get him another pair. As a result, he asked Lucas to film more [[Wikipedia:Close-up|close-up]] shots of him from the waist up and, after the director agreed, Cushing wore [[Wikipedia:Slipper|slippers]] during the scenes where his feet were not visible.<ref name="SWI80">Nasr, p. 80</ref><ref name="Nottingham">"How Jim fixed it for horror actor Cushing" (May 8, 2004). [[Wikipedia:Nottingham Post|''Nottingham Evening Post'']]: p. 16.</ref><ref>O'Brien, John ([[April 20]], [[2002]]). "Bring on the Clones". [[Wikipedia:The Courier-Mail|''The Courier-Mail'']]: p. M01.</ref> Some of the actors who appeared in scenes with Cushing had trouble not laughing because of the shoes.<ref name="SWI94" /> During rehearsals, Lucas originally planned for Tarkin and Vader to use a giant screen filled with computerized architectural representations of hallways to monitor the whereabouts of Skywalker, Solo and Organa. Although the idea was ultimately abandoned before filming began, Cushing and Prowse rehearsed those scenes in a set built by computer animation artist [[Larry Cuba]].<ref>Rinzler, p. 180</ref> The close-up shots of Cushing aboard the Death Star, shown right before the battlestation is destroyed, were actually extra footage taken from previously-shot scenes with Cushing that did not make the final film. During production, Lucas decided to add those shots, along with [[Wikipedia:Second unit|second unit]] footage of the Death Star [[Imperial gunner|gunners]] preparing to fire, to add more suspense to the film's [[Battle of Yavin|space battle]] scenes.<ref>Rinzler, p. 238</ref> |

During the filming of ''Star Wars'', Cushing was provided with a pair of boots far too small to accommodate the actor's size twelve feet. This caused a great deal of pain for him during shooting sessions, but the costume designers did not have enough time to get him another pair. As a result, he asked Lucas to film more [[Wikipedia:Close-up|close-up]] shots of him from the waist up and, after the director agreed, Cushing wore [[Wikipedia:Slipper|slippers]] during the scenes where his feet were not visible.<ref name="SWI80">Nasr, p. 80</ref><ref name="Nottingham">"How Jim fixed it for horror actor Cushing" (May 8, 2004). [[Wikipedia:Nottingham Post|''Nottingham Evening Post'']]: p. 16.</ref><ref>O'Brien, John ([[April 20]], [[2002]]). "Bring on the Clones". [[Wikipedia:The Courier-Mail|''The Courier-Mail'']]: p. M01.</ref> Some of the actors who appeared in scenes with Cushing had trouble not laughing because of the shoes.<ref name="SWI94" /> During rehearsals, Lucas originally planned for Tarkin and Vader to use a giant screen filled with computerized architectural representations of hallways to monitor the whereabouts of Skywalker, Solo and Organa. Although the idea was ultimately abandoned before filming began, Cushing and Prowse rehearsed those scenes in a set built by computer animation artist [[Larry Cuba]].<ref>Rinzler, p. 180</ref> The close-up shots of Cushing aboard the Death Star, shown right before the battlestation is destroyed, were actually extra footage taken from previously-shot scenes with Cushing that did not make the final film. During production, Lucas decided to add those shots, along with [[Wikipedia:Second unit|second unit]] footage of the Death Star [[Imperial gunner|gunners]] preparing to fire, to add more suspense to the film's [[Battle of Yavin|space battle]] scenes.<ref>Rinzler, p. 238</ref> |

||

| − | Mark Hamill did not perform in any scenes with Cushing, but Hamill was a fan of the actor and specifically sought him out to share his admiration and ask for an [[Wikipedia:Autograph|autograph]]. Hamill asked questions about Cushing's past acting career, and he asked specifically what it was like working with Laurel and Hardy in ''A Chump at Oxford''.<ref>Rinzler, p. 179</ref> When ''Star Wars'' was first released in 1977, most preliminary advertisements touted Cushing's Tarkin as the primary antagonist of the film, not Vader;<ref>[[Peter Vilmur|Vilmur, Peter]] ([[September 15]], [[2009]]). [http://www.starwars.com/vault/books/news20090911b.html "''The Complete Vader'': Author Interviews"]. ''[[StarWars.com]]'' Retrieved [[September 20]], [[2010]].</ref><ref name="NW">Kroll, Jack ([[May 30]], [[1977]]). "Fun in Space". [[Wikipedia:Newsweek|''Newsweek'']]: p. 60.</ref> in a 1977 [[Wikipedia:Newsweek|''Newsweek'']] article, writer Jack Kroll incorrectly stated that Tarkin was the leader of the Empire, and called Vader his "lieutenant."<ref name="NW" /> Cushing was extremely pleased with the final film, and he claimed his only disappointment was that Tarkin was killed and could not appear in the subsequent sequels. The film gave Cushing the highest amount of visibility of his entire career, and helped inspire younger audiences to watch his older films.<ref name="SWI80" /><ref name="Majendie">Majendie, Paul (August 7, 1986). "Master of horror tells his story." [[Wikipedia:Chicago Tribune|''Chicago Tribune'']]: p. D9.</ref> |

+ | Mark Hamill did not perform in any scenes with Cushing, but Hamill was a fan of the actor and specifically sought him out to share his admiration and ask for an [[Wikipedia:Autograph|autograph]]. Hamill asked questions about Cushing's past acting career, and he asked specifically what it was like working with Laurel and Hardy in ''A Chump at Oxford''.<ref>Rinzler, p. 179</ref> Hamill and Cushing had a lunch together on [[October 9]], 1976.<ref name="Hamill's #TrueStory">{{Twitter|HamillHimself|status/1182039498839871489|[[Mark Hamill]]|quote=I was single, living in a 1-room flat in London during the original movie. I'm in street-clothes since I wasn't working, but would come to the studio anyway, to watch them film, hang-out w/ friends & on this day in particular-have lunch w/ 1 of my idols: Peter Cushing! #TrueStory}}</ref> When ''Star Wars'' was first released in 1977, most preliminary advertisements touted Cushing's Tarkin as the primary antagonist of the film, not Vader;<ref>[[Peter Vilmur|Vilmur, Peter]] ([[September 15]], [[2009]]). [http://www.starwars.com/vault/books/news20090911b.html "''The Complete Vader'': Author Interviews"]. ''[[StarWars.com]]'' Retrieved [[September 20]], [[2010]].</ref><ref name="NW">Kroll, Jack ([[May 30]], [[1977]]). "Fun in Space". [[Wikipedia:Newsweek|''Newsweek'']]: p. 60.</ref> in a 1977 [[Wikipedia:Newsweek|''Newsweek'']] article, writer Jack Kroll incorrectly stated that Tarkin was the leader of the Empire, and called Vader his "lieutenant."<ref name="NW" /> Cushing was extremely pleased with the final film, and he claimed his only disappointment was that Tarkin was killed and could not appear in the subsequent sequels. The film gave Cushing the highest amount of visibility of his entire career, and helped inspire younger audiences to watch his older films.<ref name="SWI80" /><ref name="Majendie">Majendie, Paul (August 7, 1986). "Master of horror tells his story." [[Wikipedia:Chicago Tribune|''Chicago Tribune'']]: p. D9.</ref> |

The Tarkin character was not identified by the first name Wilhuff until the release of the [[LucasArts]] [[Wikipedia:Screensaver|screensaver]] and computer media program [[Star Wars Screen Entertainment|''Star Wars'' Screen Entertainment]] in [[1994]], the year of Cushing's death.<ref>''[[Star Wars Screen Entertainment|''Star Wars'' Screen Entertainment]] ([[1994]]). [[LucasArts]]: [[Wikipedia:CD-ROM|CD-ROM]].</ref> Years later, Cushing's friend and frequent co-star Christopher Lee would also be cast as a ''Star Wars'' character, portraying [[Count]] [[Dooku]] in the [[prequel trilogy]] films [[Star Wars: Episode II Attack of the Clones|''Attack of the Clones'']] ([[2002]]) and [[Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith|''Revenge of the Sith'']] ([[2005]]). In an interview with the magazine ''[[Star Wars Insider]]'', Lee claimed the fact that Cushing had previously appeared in ''Star Wars'' made the role that much more special to him.<ref>{{InsiderCite|51|Christopher Lee: Rings of Fire}}</ref> Wilhuff Tarkin appeared briefly in ''Revenge of the Sith'', during a scene near the end of the film as Darth Vader and the [[Galactic Emperor]] [[Darth Sidious|Palpatine]] stare at the still under-construction Death Star. Animation director [[Rob Coleman]] said the filmmakers considered creating a digital version of Peter Cushing for the scene, and discussed the idea at length with Lee because the two were such close friends.<ref name="Coleman">[[Rob Coleman|Coleman, Rob]]. ([[2005]]) (Audio commentary). [[Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith|''Star Wars'': Episode III ''Revenge of the Sith'']]. [[Wikipedia:DVD|DVD]]. [[Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation|20th Century Fox]].</ref> They also considered using unused footage of Cushing from ''Star Wars'' and digitally animating Cushing's lips to match new dialogue.<ref>[[J.W. Rinzler|Rinzler, J.W.]] ([[2005]]). ''[[The Making of Star Wars Revenge of the Sith]]''. [[Wikipedia:New York City|New York City]], [[Wikipedia:New York|New York]]: [[Del Rey]]. p. 39. [[Wikipedia:International Standard Book Number|ISBN]] [[Wikipedia:Special:BookSources/0345431383|0345431383]].</ref> However, they ultimately decided to cast actor [[Wayne Pygram]], who was fitted with [[Wikipedia:Prosthetic makeup|prosthetic makeup]] that made him very closely resemble Cushing.<ref name="Coleman" /> Starting in [[2011]], the Tarkin character also started appearing in the [[Wikipedia:Cartoon Network|Cartoon Network]] animated television series [[Star Wars: The Clone Wars (TV series)|''Star Wars: The Clone Wars'']]. The character was designed by sculptor [[Darren Marshall]], who based him on Cushing's image. Marshall said he grew up with the Hammer films, and admired the talents and expressive faces of both Cushing and Lee.<ref>{{InsiderCite|124|Making Maquettes}}</ref> [[Stephen Stanton]], the voice actor who portrayed Tarkin in the show, said he researched Cushing's performances in the Hammer films, then tried to imitate what Cushing might have sounded like in his mid-thirties and softened it to give a level of humanity to Tarkin.<ref>[[Peter Vilmur|Vilmur, Peter]] ([[March 3]], [[2011]]). [http://www.starwars.com/theclonewars/stephen_stanton_as_tarkin/index.html "Look Who's Tarkin: Stephen Stanton"]. ''[[StarWars.com]]'' Retrieved [[March 4]], [[2011]].</ref> |

The Tarkin character was not identified by the first name Wilhuff until the release of the [[LucasArts]] [[Wikipedia:Screensaver|screensaver]] and computer media program [[Star Wars Screen Entertainment|''Star Wars'' Screen Entertainment]] in [[1994]], the year of Cushing's death.<ref>''[[Star Wars Screen Entertainment|''Star Wars'' Screen Entertainment]] ([[1994]]). [[LucasArts]]: [[Wikipedia:CD-ROM|CD-ROM]].</ref> Years later, Cushing's friend and frequent co-star Christopher Lee would also be cast as a ''Star Wars'' character, portraying [[Count]] [[Dooku]] in the [[prequel trilogy]] films [[Star Wars: Episode II Attack of the Clones|''Attack of the Clones'']] ([[2002]]) and [[Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith|''Revenge of the Sith'']] ([[2005]]). In an interview with the magazine ''[[Star Wars Insider]]'', Lee claimed the fact that Cushing had previously appeared in ''Star Wars'' made the role that much more special to him.<ref>{{InsiderCite|51|Christopher Lee: Rings of Fire}}</ref> Wilhuff Tarkin appeared briefly in ''Revenge of the Sith'', during a scene near the end of the film as Darth Vader and the [[Galactic Emperor]] [[Darth Sidious|Palpatine]] stare at the still under-construction Death Star. Animation director [[Rob Coleman]] said the filmmakers considered creating a digital version of Peter Cushing for the scene, and discussed the idea at length with Lee because the two were such close friends.<ref name="Coleman">[[Rob Coleman|Coleman, Rob]]. ([[2005]]) (Audio commentary). [[Star Wars: Episode III Revenge of the Sith|''Star Wars'': Episode III ''Revenge of the Sith'']]. [[Wikipedia:DVD|DVD]]. [[Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation|20th Century Fox]].</ref> They also considered using unused footage of Cushing from ''Star Wars'' and digitally animating Cushing's lips to match new dialogue.<ref>[[J.W. Rinzler|Rinzler, J.W.]] ([[2005]]). ''[[The Making of Star Wars Revenge of the Sith]]''. [[Wikipedia:New York City|New York City]], [[Wikipedia:New York|New York]]: [[Del Rey]]. p. 39. [[Wikipedia:International Standard Book Number|ISBN]] [[Wikipedia:Special:BookSources/0345431383|0345431383]].</ref> However, they ultimately decided to cast actor [[Wayne Pygram]], who was fitted with [[Wikipedia:Prosthetic makeup|prosthetic makeup]] that made him very closely resemble Cushing.<ref name="Coleman" /> Starting in [[2011]], the Tarkin character also started appearing in the [[Wikipedia:Cartoon Network|Cartoon Network]] animated television series [[Star Wars: The Clone Wars (TV series)|''Star Wars: The Clone Wars'']]. The character was designed by sculptor [[Darren Marshall]], who based him on Cushing's image. Marshall said he grew up with the Hammer films, and admired the talents and expressive faces of both Cushing and Lee.<ref>{{InsiderCite|124|Making Maquettes}}</ref> [[Stephen Stanton]], the voice actor who portrayed Tarkin in the show, said he researched Cushing's performances in the Hammer films, then tried to imitate what Cushing might have sounded like in his mid-thirties and softened it to give a level of humanity to Tarkin.<ref>[[Peter Vilmur|Vilmur, Peter]] ([[March 3]], [[2011]]). [http://www.starwars.com/theclonewars/stephen_stanton_as_tarkin/index.html "Look Who's Tarkin: Stephen Stanton"]. ''[[StarWars.com]]'' Retrieved [[March 4]], [[2011]].</ref> |

||

Revision as of 01:30, 10 October 2019

Warning: This infobox has missing parameters: listedpronouns and unrecognized parameters: other, SW, voice

- "My criterion for accepting a role isn't based on what I would like to do. I try to consider what the audience would like to see me do and I thought kids would adore Star Wars."

- ―Peter Cushing

Peter Cushing (May 26, 1913–August 11, 1994) was an English actor best known for his roles in the Hammer Studios horror films of the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, as well as his performance as Grand Moff Wilhuff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977). Spanning over six decades, his acting career included appearances in more than 100 films, as well as many television, stage and radio roles. Born in Kenley, Surrey, Cushing made his stage debut in 1935 and spent three years at a repertory theater before moving to Hollywood to pursue a film career.

After making his motion picture debut in the 1939 film The Man in the Iron Mask, Cushing began to find modest success in American films before returning to England at the outbreak of World War II. Despite performing in a string of roles, including one as Osric in Laurence Olivier's film adaptation of Hamlet (1948), Cushing struggled greatly to find work during this period and began to consider himself a failure. His career was revitalized once he started to work in live television plays, and he soon became one of the most recognizable faces in British television. He earned particular acclaim for his lead performance in a 1954 adaptation of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four. Cushing gained worldwide fame for his appearances in twenty-two horror films by the independent Hammer Studios, particularly for his role as Baron Victor Frankenstein in six of their seven Frankenstein films, and Dr. Van Helsing in five Dracula films. Cushing often starred alongside actor Christopher Lee, who became one of his closest friends.

Cushing appeared in several other Hammer Studios films, including The Abominable Snowman, The Mummy and The Hound of the Baskervilles, the last of which marked the first of many times he portrayed the famous detective Sherlock Holmes throughout his career. Cushing continued to perform a variety of roles, although he was often typecast as a horror film actor. He gained the highest amount of visibility in his career in 1977, when he appeared as Grand Moff Tarkin in the first Star Wars film. Director George Lucas wanted a particularly strong actor for the part and Cushing was his first choice, although the actor claimed he was initially approached to play the Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi. Cushing continued acting into his later years, until his death in 1994 due to prostate cancer. He wrote two autobiographies and was fiercely devoted to his wife of twenty-eight years, Helen Cushing, who died in 1971.

Biography

Early life

- "As far back as I can ever remember, without really knowing it I wanted to be an actor. I was always dressing up, you know, playing pretend, putting on mothers hats and things. I'm sure Freud would have something to say about that. It was very much in my blood."

- ―Peter Cushing

Peter Wilton Cushing was born in Kenley, a district in the English county of Surrey, on May 26, 1913 to George Edward Cushing and Nellie Marie Cushing, nee King. The youngest of two boys—his brother George was three years older—his mother had so hoped for a daughter that for the first few years of his life, she would dress Peter in girls' frocks, let his hair grow in long curls and tie them in bows of pink ribbon, so others would often mistake him for a girl. His father, a quantity surveyor from an upper-class family, was a reserved and uncommunicative man who Peter claimed he never got to know very well. His mother was the daughter of a carpet merchant and considered of a lower class than her husband.[1] Cushing's family consisted of several stage actors, including his paternal grandfather Henry William Cushing (who toured with Sir Henry Irving),[10] his paternal aunt Maude Ashton and his step-uncle Wilton Herriot, after whom Peter Cushing received his middle name.[1]

Peter Cushing in 1922, at age nine

The Cushing family lived in Dulwich during World War I, but moved to Purley after the war ended in 1918.[11] Although raised during wartime, Cushing was too young to understand or become greatly affected by it, and was shielded from the horrors of war by his mother, who encouraged him to play games under the kitchen table whenever the threat of possible bombings arose.[1] In his infancy, Cushing twice developed pnuemonia and once what was then known as "double pneumonia." Although he survived, the latter was often fatal during that period.[11] During one Christmas in his youth, Cushing saw a stage production of Peter Pan, which served as an early source of inspiration and interest toward acting.[12] Cushing loved dressing up and playing pretend from an early age, and later claimed he always wanted to be an actor, "perhaps without knowing at first."[13] A fan of comics and toy collectibles in his youth, Cushing earned money by staging puppet shows for family members with his glove-puppets and toys.[14]

He began his early education in Dulwich, an affluent area of South London, before attending the Shoreham Grammar School in Shoreham-by-Sea, on the Sussex coast between Brighton and Worthing. Prone to homesickness, he was miserable at the boarding school and spent only one term there before returning home.[15] He attended the Purley County Secondary School, where he swam and played cricket and rugby.[11] With the exception of art, Cushing was a self-proclaimed poor student in most subjects and had little attention span for that which did not interest him. He got fair grades only through the help of his brother, a strong student who did his homework for him.[13] Cushing harbored aspirations for the arts all throughout his youth, especially acting. His childhood inspiration was Tom Mix, an American film actor and star of many Western films.[16] D.J. Davies, the Purley County Secondary School physics teacher who produced all the school's plays, recognized some acting potential in him and encouraged him to participate in the theater, even allowing Cushing to skip class to paint sets. He played the lead in nearly every school production during his teenage years, including the role of Sir Anthony Absolute in a 1929 staging of Richard Brinsley Sheridan's comedy of manners play, The Rivals.[17]

Cushing wanted to enter the acting profession after school, but his father opposed the idea, despite the theatrical background of several of his family members. Instead, seizing upon Cushing's interest in art and drawing, he got his son a job as a surveyor's assistant in the drawing department of the Couldsdon and Purley Urban District Council's surveyor's office during the summer of 1933.[17] Cushing hated the job, where he remained for three years without promotion or advancement due to his lack of ambition in the profession. The only enjoyment he got out of it was drawing prospectives of proposed buildings, which were almost always rejected because they were too imaginative and expensive and lacked strong foundations, which Cushing disregarded as a "mere detail." Thanks to his former teacher Davies, Cushing continued to appear in school productions during this time, as well as amateur plays such as W.S. Gilbert's Pygmalion and Galatea,[18] George Kelly's The Torch-Bearers, and The Red Umbrella, by Brenda Girvin and Monica Cosens.[19] Cushing would often learn and practice his lines in an attic at work, under the guise that he was putting ordnance survey maps into order. He would regularly apply for auditions and openings for roles he found in the arts-oriented newspaper The Stage, but was turned down repeatedly due to his lack of professional experience in the theater.[18]

Early career

- "That I should turn up at the precise moment was one of those extraordinarily lucky breaks which we all need at some time or other during this life, but don't always get."

- ―Peter Cushing, regarding The Man in the Iron Mask[20]

Cushing eventually applied for a scholarship at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London.[21] His first audition was before the actor Allan Aynesworth, who was so unimpressed with Cushing's manner of speech that he rejected him outright and insisted he not return until he improved his diction.[19][22] Cushing continued to persistently pursue a scholarship, writing exactly twenty-one letters to the school,[22] until actor and producer Bill Fraser finally agreed to meet Cushing in 1935 simply so he could ask him in person to stop writing. During that meeting, Cushing was given a walk-on part as a courier in that night's production of J. B. Priestley's Cornelius. This marked his professional stage debut, although he had no lines and did little more than stand on stage behind other actors. Afterward, he was granted the scholarship and given odd jobs around the theater, such as selling refreshments and working as an assistant stage manager.[19] One of his earliest professional stage performances was in 1935 as Captain Randall in Ian Hay's The Middle Watch at the Connaught Theatre in Worthing.[23] By the end of the summer of 1936, Cushing accepted a job with the repertory theater company Southampton Rep., working as assistant stage manager and performing in bit roles at the Grand Theatre in the Hampshire city.[19] He spent the next three years in an apprenticeship at Southampton Rep.,[16] auditioning for character roles both there and in other surrounding theaters, eventually amassing almost 100 individual parts.[19][24]

In his first film job, Peter Cushing worked as a stand-in for Louis Hayward (left) in the shooting of The Man in the Iron Mask (1939).

Soon, he felt the urge to pursue a film career in the United States. In 1939, his father bought him a one-way ticket to Hollywood, where he moved with only £50 to his name.[16] Cushing met a Colombia Pictures employee named Larry Goodkind, who wrote him a letter of recommendation and directed him to acquaintances Goodkind knew at the company Edward Small Productions. Cushing visited the company, which was only a few days away from filming the 1939 film The Man in the Iron Mask, the James Whale-directed adaptation of the Alexandre Dumas tale based on the French legend of a prisoner during the reign of Louis XIV of France.[20] Cushing was hired as a stand-in for scenes that featured both characters played by Louis Hayward, who had the dual lead roles of King Louis XIV and Philippe of Gascony. Cushing would play one part against Hayward in one scene, then the opposite part in another, and ultimately the scenes would be spliced together in a split screen process that featured Hayward in both parts and left Cushing's work cut from the film altogether.[24] Although the job meant Cushing would receive no actual screen time, he was eventually cast in a bit part himself as the king's messenger, which made The Man in the Iron Mask his official film debut.[3] The small role involved sword-fighting and, although Cushing had no experience with fencing, he told Whale he was an excellent fencer to ensure he got the part. Cushing later said his unscreened scenes alongside Hayward were terrible performances, but that his experience on the film provided an excellent opportunity to learn and observe how filming on a studio set worked.[20]

Only a few days after filming on The Man in the Iron Mask was complete, Cushing was in the Schwab's Drug Store, a famous Sunset Boulevard hangout spot for actors, when he learned producer Hal Roach was seeking an English actor for a comedy film starring Laurel and Hardy. Cushing sought and was cast in the role. Cushing appeared only briefly in A Chump at Oxford (1940) and his scenes took just one week to film, but he was proud to work with who he called "two of the greatest comedians the cinema has ever produced."[4] Around this time actor Robert Coote, who met Cushing during a cricket game, recommended to director George Stevens that Cushing might be good for a part in Stevens' upcoming film Vigil in the Night (1940). Adapted from a serial novella of the same name, it was a drama film about a nurse played by Carole Lombard working in a poorly-equipped country hospital. Stevens cast Cushing in the second male lead role of Joe Shand, the husband of the Lombard character's sister. Shooting ran from September to November 1939,[25] and the film was released in 1940, drawing Cushing's first semblance of attention and critical praise.[16]

Cushing continued to work in a few Hollywood engagements, including an uncredited role in the war film They Dare Not Love (1941), which reunited him with director James Whale. In 1941, Cushing was cast in one of a series of short films in the MGM series The Passing Parade, which focused on strange-but-true historical events. He appeared in the episode Your Hidden Master as a young Clive of India, well before the soldier established the military and political supremacy of the East India Company. In the film, Clive tries to shoot himself twice but the gun misfires, then he fires a third time at a pitcher of water and the gun works perfectly. Clive takes this to be an omen that he should live, and he goes on to perform great feats in his life. Studio executives were pleased with Cushing's performance, and there was talk among Hollywood insiders grooming him for stardom.[26] Despite the success he was starting to enjoy, however, Cushing grew homesick and decided he wished to return to England. He moved to New York City in anticipation of his eventual return home, during which time he voiced a few radio commercials and joined a summer stock theater company to raise money for his voyage back to England. He performed in such plays as Robert E. Sherwood's The Petrified Forest, Arnold Ridley's The Ghost Train, S. N. Behrman's Biography and a modern-dress version of William Shakespeare's Macbeth. He was eventually noticed by a Broadway theater talent scout,[27] and in 1941 he made his Broadway debut in the religious wartime drama The Seventh Trumpet. It received poor reviews, however, and ran for only eleven days.[24]

Return to England

- "Why don't you get some other job to do when you are disengaged, like your grandfather? You could become a front-of-house manager, for instance. I could lend you my evening clothes. You are nearly 40, and a failure."

- ―Peter Cushing's father-in-law, during a bad period in Cushing's career[28]

Cushing returned to England during World War II. Although some childhood injuries prevented him from serving on active duty,[16] a friend suggested he entertain the troops by performing as part of the Entertainments National Service Association.[22] In 1942, the Noel Coward play Private Lives was touring the military stations and hospitals in the British Isles, and the actor playing the lead role of Elyot Chase was called to service. Cushing agreed to take his place with very little notice or time to prepare, and earned a salary of ten pounds a week for the job.[29] During this tour he met Helen Beck, a former dancer who was starring in the lead female role of Amanda Prynne.[21][30] They fell in love and were married on April 10, 1943.[31] Cushing eventually had to leave the ENSA due to lung congestion, an ailment his wife helped him recover from.[22] The two had little money around this time, and Cushing had to collect from both National Assistance and the Actors Benevolent Fund. Cushing struggled to find work during this period, with some plays he was cast in failing to even make it past rehearsals into theaters. Others closed after a few showings, like an ambitious five-hour stage adaptation of Leo Tolstoy's novel War and Peace that opened and closed in 1943 in London's Phoenix Theatre.[31]

Cushing recorded occasional radio spots and appeared in week-long stints as a featured player in London's Q Theatre, but otherwise work was difficult to come by.[24] Cushing found a modest success in a 1945 production of Sheridan's The Rivals at Westminster's Criterion Theatre, which earned him enough money to pay off some growing debts.[32] The war years continued to prove difficult for him, however, and at one point he was forced to work designing ladies head-scarves at a Macclesfield-based silk manufacturer to make ends meet.[24] In the autumn of 1946, after the war ended, Cushing unsuccessfully auditioned for the part of Paul Verrall in a stage production of the play Born Yesterday that was being staged by famed actor and director Laurence Olivier. He was not cast because he insisted he could not perform in an American accent.[24] After Cushing attempted the accent and failed, Olivier replied, "Well, I appreciate you not wasting my time. I shall remember you."[33] Nearing middle age and finding it increasingly harder to make a living in acting, Cushing began to consider himself a failure.[2]

Peter Cushing as Osric alongside Laurence Olivier (right), who played the title role in his 1948 film adaptation of William Shakespeare's Hamlet

In 1947, when Laurence Olivier sought him out to adapt the William Shakespeare play Hamlet into a film, Cushing's wife Helen pushed him to pursue a role.[16] Far from being deterred by Cushing's unsuccessful audition the year before, Olivier remembered the actor well and was happy to cast him,[24][16] but the only character left unfilled was the relatively small part of the foppish courtier Osric.[16] Cushing accepted the role, and Hamlet (1948) marked his British film debut.[3] One of Cushing's primary scenes involved Osric talking to Hamlet and Horatio while walking down a wide stone spiral stairway. The set provided technical difficulties, and all of Cushing's lines had to be rerecorded later as part of a post-synching process. Cushing had recently undergone dental surgery and he was trying not to open his mouth widely for fear of spitting. When this hindered the post-synching process, Olivier leaned in close to Cushing's face and said, "Now drown me. It'll be a glorious death, so long as I can hear what you're saying."[34]

Hamlet went on to win the Academy Award for Best Picture, and earned Cushing praise for his performance.[21] Also appearing in the film was Christopher Lee, who would eventually become a close friend and frequent co-star with Cushing.[35] Cushing designed custom hand-scarves in honor of the Hamlet film, and as it was being exhibited across England, the scarves were eventually accepted as gifts by Queen Mother Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon and Queen Elizabeth II.[22] After Hamlet, both Peter and Helen Cushing accepted a personal invitation from Olivier to join Old Vic, Olivier's repertory theater company, which embarked on a year-long tour of Australasia.[24] The tour, which lasted until February 1949, took them to Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Hobart, Tasmania, Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin, and included performances of Richard Brinsley Sheridan's The School for Scandal, Shakespeare's Richard III, Thornton Wilder's The Skin of Our Teeth, Jean Anouilh's Antigone and Anton Chekhov's The Proposal.[36]

Success in television

- "Peter, you are unaware of your own value, and what your name means to people. They will be only too glad to have you work for them. You'll see."

- ―Peter Cushing's wife, Helen, encouraging him to seek television work[37]

Cushing struggled greatly to find work over the next few years, and became so stressed that he felt he was suffering from an extended nervous breakdown.[36] Nevertheless, he continued to appear in several small roles in radio, theater and film.[5][16] Among them was the 1952 John Huston film Moulin Rouge, where he played a racing spectator named Marcel de la Voisier appearing opposite star José Ferrer, who played the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.[3] During this discouraging period for Cushing, his wife encouraged him to seek roles in television, which was only just starting to grow in popularity in England.[2] She suggested he write to all the producers listed in the Radio Times magazine seeking work in the medium. The move proved to be a wise one, as Cushing was hired to fill out the cast of a string of major theater successes that were being adapted to live television. The first was J. B. Priestley's Eden End, which was televised in December 1951. Over the next three years, he became one of the most active and favored names in British television,[2][5][22] and was considered a pioneer in British television drama.[3][30]

Peter Cushing was widely acclaimed for his performance in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1954), a live televised play based on the original George Orwell novel.

He earned praise for playing the lead male role of Fitzwilliam Darcy in the BBC's 1952 television miniseries production of Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice.[38] Other successful television ventures during this time included Epitaph for a Spy, The Noble Spaniard, Beau Brummell,[5] Portrait by Peko,[39] and Anastasia, the latter of which won Cushing the Daily Mail National Television Award for Best Actor of 1953-54.[5] His largest television success from this period was the leading role of Winston Smith in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Rudolph Cartier's 1954 British television adaptation of George Orwell's classic novel of the same name about a totalitarian socialist regime. The production would prove to be controversial, resulting in death threats for Cartier and causing Cushing to be vilified for appearing in such "filth."[5] Parliament even considered a motion immediately after the first screening to ban the play's live repeat.[5][30] Nevertheless, a second televised production was filmed and aired, and Cushing eventually drew both critical praise and acting awards, further cementing his reputation as one of Britain's biggest television stars.[2] Cushing felt his first performance was much stronger than the second, but the second production is the only known surviving version.[40]

In the two years following Nineteen Eighty-Four, Cushing appeared in thirty-one television plays and two serials, and won Best Television Actor of the Year from the Evening Chronicle. He also won best actor awards from the Guild of Television Producers in 1955,[41] and from the British Academy of Film and Television Arts in 1956.[42] Among the plays he appeared in during this time were Terence Rattigan's The Browning Version, Gordon Daviot's Richard of Bordeaux, and a 1955 production of Nigel Kneale's The Creature,[5] the latter of which Cushing would star in a film adaptation two years later.[7] Despite this continued success in live television, Cushing found the medium too stressful and wished to return to film.[2] Cinematic roles proved somewhat difficult to find, however, as film producers were often resentful of television stars for drawing audiences away from the cinema.[43]

Nevertheless, he continued to work in some film roles during this period, including the adventure film The Black Knight (1954) opposite Alan Ladd.[41] For that film, he traveled to Spain and filmed scenes on location in the castles of Manzanares el Real and El Escorial.[44] He also starred in the 1955 film adaptation of the Graham Greene novel The End of the Affair as Henry Miles, an important civil servant and the cuckolded husband of Sarah Miles, played by Deborah Kerr.[3] Also that year he appeared in Magic Fire, an autobiographical film about the German composer Richard Wagner. Filmed on location in Munich, Cushing played Otto Wesendonck, the husband of poet Mathilde Wesendonck, who in the film is portrayed as having an affair with Wagner.[45]

Hammer Studios' Frankenstein films

- "Cushing turned the part of Baron Frankenstein into a myth of his own, a persona which would forever be connected with the actor's chilling likeness. Cold and calculating, his Baron would be a distant cousin to Grand Moff Tarkin"

- ―Star Wars Insider writer Constantine Nasr

Peter Cushing received worldwide fame from his performances as Baron Victor Frankenstein in the Hammer Studios Frankenstein films.

During a brief quiet period following Cushing's television success, he read in trade publications about Hammer Studios, a low-budget independent production company seeking to adapt Mary Shelly's horror novel Frankenstein into a new film.[41] Cushing, who enjoyed the tale as a child,[2] dispatched his agent John Redway to inform the company of Cushing's interest in playing the protagonist, Baron Victor Frankenstein. The studio executives were anxious to have Cushing; in fact, Hammer co-founder James Carreras had been unsuccessfully courting Cushing for film roles in other projects even before his major success with Nineteen Eighty-Four. Cushing was about twenty years older than Baron Frankenstein as he appeared in the original novel, but that did not deter the filmmakers.[41] Cushing was cast in the lead role of The Curse of Frankenstein (1957), marking the first of twenty-two films he made with Hammer Studios.[6]

Unlike the well-known Frankenstein film from 1931 by Universal Studios, the Hammer films revolved mainly around Victor Frankenstein, rather than his monster.[46] Screenwriter Jimmy Sangster wrote the protagonist as an ambitious, egotistical and coldly intellectual scientist who despised his contemporaries.[41] Unlike the character from the novel and past film versions, Cushing's Frankenstein commits vicious crimes to attain his goals, including the murder of a colleague to obtain a brain for his creature.[46] The Curse of Frankenstein also starred Cushing's old Hamlet co-star Christopher Lee, who played Frankenstein's monster.[3] Cushing and Lee became extremely close friends, and would remain so for the rest of Cushing's life. They first met on the set of the film, where Lee was still wearing the monster make-up prepared by Phil Leakey. Hammer Studios' publicity department put out a story that when Cushing first encountered Lee without the make-up on, he screamed in terror.[47]

Cushing so valued preparation for his role that he insisted on being trained by a surgeon to learn how to wield a scalpel authentically.[30] Shot in dynamic color with a small £65,000-budget, the film was noted for its heavy usage of gore and sexual content.[2] As a result, while the film did well at the box office with its target audience, it drew mixed to negative reviews from professional critics. Most, however, were complimentary of Cushing's performance,[48] claiming it added a layer of distinction and credibility to the film.[49] Many felt Cushing's performance helped create the archetypal mad scientist character.[30] Picturegoer writer Margaret Hinxman, who was not complimentary of Lee's performance, praised Cushing and wrote of the film: "Although this shocker may not have created much of a monster, it may well have created something more lasting: a star!"[48] Donald F. Glut, a writer and filmmaker who wrote a book about the portrayals of Frankenstein, said the inner warmth of Cushing's off-screen personality was apparent on-screen even despite the horrific elements of Dr. Frankenstein, which helped add a layer of likability to the character.[50]

The Curse of Frankenstein was an overnight success, launching both Cushing and Lee into a level of world-wide fame they had never previously known.[3][51] The two men would continue to work together in many films at Hammer Studios, and their names became synonymous with the company. Cushing reprised the role of Baron Victor Frankenstein in five sequels.[3] In the first, The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), his protagonist is sentence to death by guillotine, but he flees and hides under the alias Dr. Stein.[3] He returned for The Evil of Frankenstien (1963), where the Baron has a carnival hypnotist resurrect the monster's inactive brain;[52] and Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), in which the Frankenstein's monster is reincarnated as a woman played by Playboy magazine centerfold model Susan Denberg. Cushing played the lead role twice more in Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969) and Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1970).[3] The former film originally featured a scene with Cushing's Dr. Frankenstein raping the character played by Veronica Carlson. Neither Carlson nor Cushing wanted to do the scene, and the filming of it was so awkward that director Terence Fisher ended it in mid-session, and the sequence was not used in the final film.[53] In Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell, Cushing portrayed the Frankenstein doctor as completely mad, a departure from the previous movies. That film featured David Prowse as the monster; the actor would later go on to play Darth Vader alongside Cushing in Star Wars (1977).[54][55]

Hammer Studios' Dracula films

- "As for that old blood-sucker Dracula, whatever I did to get rid of him, he would keep turning up again, like a bad penny. There was no stopping him — a glutton for punishment as well as gore."

- ―Peter Cushing[56]

Peter Cushing portrayed Dr. Van Helsing in the Hammer Studios adaptation of Dracula (1958).

When Hammer Studios sought to adapt Bram Stoker's classic vampire novel Dracula to film, they cast Cushing to play the vampire's arch-nemesis Dr. Van Helsing. Cushing envisioned the character as an idealist warrior for the greater good, and sought to infuse the common decency and good-naturedness he tried to practice in his personal life into the role.[2] Cushing studied the original Stoker novels carefully and adapted several of Van Helsing's characteristics from the books into his performance, including the repeated gesture of raising his index finger to emphasize an important point.[57] Cushing said one of the biggest challenges during filming was not missing whenever he struck a prop stake with a mallet and drove it into a vampire's heart.[56] Dracula was released in 1958, with Cushing once again starring opposite Lee, who played the title character, although Cushing was given top top billing.[58] During filming, Cushing himself suggested the staging for the final confrontation scene, in which Van Helsing leaps onto a large dining room table, opens window curtains to weaken Dracula with sunlight, then uses two candlesticks as a makeshift crucifix to hold the vampire off until he dies.[2] As with the Frankenstein films, critics largely panned Dracula for its violence and sexual content, deeming it inferior to the 1931 Universal Studios version. Nevertheless, it performed well at the box office, grossing more than that year's release of Vertigo, which was directed by the famous and popular Alfred Hitchcock.[59]

In 1959, Cushing agreed to reprise the role of Dr. Van Helsing in the sequel, The Brides of Dracula (1960). Before filming began, however, Cushing said he would not participate because he did not like the script written by Jimmy Sangster and Peter Bryan. As a result, screenwriter Edward Percy was brought in to make modifications to the script. Ultimately Cushing agreed to perform, but the rewrites pushed filming into early 1960 and brought additional costs to the production.[60] Cushing was later approached to star in the 1966 sequel, Dracula: Prince of Darkness, but he turned it down due to other commitments. However, Cushing granted permission for his image to be used in the opening scene, which included archived footage from the first Dracula film. In exchange, Hammer Studios surprised Cushing by paying for extensive roofing repair work that had recently been done on Cushing's newly purchased London home.[61] In 1972, Cushing appeared in Dracula A.D. 1972, a Hammer modernization of the Dracula story set in a then-present day 1970s setting. Lee once again starred as Dracula. In the opening scene, Cushing portrays Dr. Van Helsing as he did in the previous films, and the character is killed after a fight with Dracula. The rest of the film jumps forward in time, where Cushing plays the original character's descendant, Lorrimer Van Helsing.[3] Cushing performed many of his own stunts in Dracula A.D. 1972, which included tumbling off a haywagon during a fight with Dracula. Christopher Neame, who also starred in the film, said he was particularly impressed with Cushing's agility and fitness, considering his age.[62] Cushing and Lee both reprised their respective Dracula roles in the 1974 sequel The Satanic Rites of Dracula, which was known in the United States as Count Dracula and his Vampire Bride.[3] Also that year Cushing played Lawrence Van Helsing, another descendant of Abraham Van Helsing, in The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires, a co-production between Hammer Studios and the Shaw Brothers Studio, which brought Chinese martial arts into the Dracula story.[3] In that film, Cushing's Van Helsing travels to the Chinese city Chungking, where Count Dracula is heading a vampire cult.[63]

Hammer Studios: Other roles

- "His gaunt figure, gentlemanly demeanor and controlled acting brought a chilling power to his portrayals in the British-made Hammer horror films that began in the 1950s."

- ―Salt Lake Tribune[23]

Although most well-known for his roles in the Frankenstein and Dracula films, Cushing appeared in a wide variety of other Hammer Studios productions during this time. Both he and his wife feared Cushing would become typecast into horror roles, but he continued to take them because he needed the money for Helen, who was in a constant state of poor health and required much medical attention.[43][64] He appeared in the 1957 horror film The Abominable Snowman, a Hammer Studios adaptation of a BBC Sunday Night Theatre television play from 1955, which Cushing had also starred in. He portrayed an English anthropologist searching the Himalayas for the legendary Yeti.[7] Director Val Guest said he was particularly impressed with Cushing's preparation and ability to plan which props to best use to enhance his performance, so much so that Cushing started to become known as "Props Peter".[65] In 1959, Cushing and Christopher Lee appeared in the Hammer Studios horror film The Mummy, with Cushing as the archaeologist John Banning and Lee as the antagonist Kharis.[2] Cushing saw a promotional poster for The Mummy that showed Lee's character with a large hole in his chest, allowing a beam of light to pass through his body. There was no reference to such an injury in the film, and when he asked the publicity department why it was on the poster, they said it was simply meant to serve as a shocking image to promote the movie. Cushing found this deplorable because he believed audiences would feel cheated. During filming he asked director Terence Fisher for permission to drive a harpoon through the mummy's body during a fight scene, in order to explain the poster image. Fisher agreed, and the scene was used in the film.[66]

Peter Cushing played the famous detective Sherlock Holmes, one of his favorite roles, in the Hammer Studios film The Hound of the Baskervilles (1959).

Also in 1959, he portrayed the famous detective Sherlock Holmes in the Hammer Studios production of The Hound of the Baskervilles, an adaptation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's novel of the same name.[3] He once again co-starred opposite Lee, who portrayed the aristocratic Sir Henry Baskerville.[35] An ardent fan of Sherlock Holmes, Cushing was highly anxious to play the character,[67] and reread the novels in anticipation of the role.[68] Hammer Studios decided to heighten the source novel's horror elements, which upset the estate of Conan Doyle, but Cushing himself voiced no objection to the creative license because he felt the character of Holmes himself remained intact. However, when producer Anthony Hinds proposed removing the character's deerstalker, Cushing insisted they remain because audiences associated Holmes with his headgear and pipes.[69] Cushing prepared extensively for the role, studying the novel and taking notes in his script. He scrutinized the costumes and scoured over screenwriter Peter Bryan's script, often altering words or phrases.[70] Lee later claimed to be awestruck by Cushing's ability to incorporate many different props and actions into his performance simultaneously, whether reading, smoking a pipe, drinking whiskey, filing through papers or other things while portraying Holmes.[71] In later years, Cushing considered his Holmes performance one of the proudest accomplishments of his career.[67] Cushing drew generally mixed reviews: Film Daily called it a "tantalising performance" and Time Out's David Pirie called it "one of his very best performances",[72] while the Monthly Film Bulletin called him "tiresomely mannered and too lightweight" and BBC Television's Barry Norman said he "didn't quite capture the air of know-all arrogance that was the great detective's hallmark".[73] The Hound of the Baskervilles was originally conceived as the first in a series of Sherlock Holmes films, but no sequels were made.[66]

Immediately upon completion of The Hound of the Baskervilles, Cushing was offered the lead role in the Hammer film The Man Who Could Cheat Death, originally conceived as a remake of the Oscar Wilde novel The Picture of Dorian Gray. Cushing turned it down, in part because he felt he did not have enough time to prepare for the role, in part because he feared becoming typecast into horror films, and in part because he did not like the script by Jimmy Sangster.[74] James Carreras, who sold the film to Paramount Pictures in part based on the strength of Cushing's anticipated participation, was infuriated with the actor and issued a legal threat to him demanding he behave with more circumspection in the future regarding role offerings. The move created a rift between Cushing and Carreras, and contributed to a slight decline in the frequency of Cushing's participation with the studio.[75]

In 1960, Cushing played the Sheriff of Nottingham in the Hammer Studios adventure film Sword of Sherwood Forest, which starred Richard Greene as the legendary outlaw Robin Hood.[3] It was filmed on location in County Wicklow in the Republic of Ireland.[76] The next year, Cushing starred as an Ebenezer Scrooge-like manager of a bank being robbed in the Hammer Studios thriller film Cash on Demand (1961). Cushing considered this among the favorites of his films,[3] and some critics believed it to be among his best performances, although it was one of the least seen films from his career.[2] In 1962, he appeared in the Hammer Studios film Captain Clegg, known in the United States as Night Creatures. Cushing starred as Parson Blyss, the local reverend of an 18th century English coastal town believed to be hiding his smuggling activities with reports of ghosts.[3] The film was roughly based on the Doctor Syn novels by Russell Thorndike. Cushing read Thorndike to prepare for the role, and made suggestions to make-up artist Roy Ashton about Blyss' costume and hairstyle.[77] Cushing and director Peter Graham Scott did not get along well during filming and at one point, when the two were having a disagreement on set, Cushing turned to cameraman Len Harris and said, "Take no notice Len. We've done enough of these now to know what we're doing."[77]

Cushing and Lee appeared together in the studio's 1964 horror film The Gorgon, about the female snake-haired Gorgon character from Greek mythology. The next year, Cushing and Lee yet again appeared together in the Hammer film She, about a lost realm ruled by the immortal queen Ayesha, played by Ursula Andress. Cushing later appeared in The Vampire Lovers (1970), an erotic Hammer Studios horror film about lesbian vampires, adapted in part from the Sheridan Le Fanu novella Carmilla.[2] The next year he was set to star in a sequel, Lust for a Vampire, but had to drop out because his wife was ill. His role was filled instead by actor Ralph Bates.[66] Later that year, however, Cushing stared in Twins of Evil, a prequel of sorts to The Vampire Lovers, as Gustav Weil, the leader of a group of religious puritans trying to stamp out witchcraft and satanism.[78] Among his final Hammer roles was Fear in the Night (1972), where he played a one-armed school headmaster apparently terrorizing the protagonist, played by Judy Geeson.[79]

Non-Hammer Studios work

- "That character of his always shined through in all of his movies. No matter how mean they were supposed to be, you always felt that underneath the makeup or acting was a real Santa Claus character. That's certainly true of Peter Cushing."

- ―Forrest J Ackerman

A publicity image of Peter Cushing from 1960

Although widely known for his Hammer Studios performances from the 1950s to the 1970s, Cushing worked in a variety of other roles during this time, and actively sought roles outside the horror genre to diversify his work.[2] He continued to perform in occasional stage productions, such as Robert E. MacEnroe's The Silver Whistle at Westminster's Duchess Theatre in 1956.[80] Also that year he appeared in the film Alexander the Great as the Athenian General Memnon of Rhodes. The battle scenes, in which Cushing's character is slain by Richard Burton's Alexander the Great, were filmed in the Spanish autonomous community of Andalusia.[45] In 1959, Cushing originally planned to appear in the lead role of William Fairchild's play The Sound of Murder, while shooting a film at the same time. The hectic schedule became overbearing for Cushing, who had to drop out of the play and resolved to never again attempt a film and play simultaneously.[81]

He appeared in the biographical epic film John Paul Jones (1959), in which Robert Stack played the title role of the American naval fighter in the American Revolutionary War.[3] Cushing became very ill with dysentery during filming and lost a considerable amount of weight as a result.[82] In 1960, Cushing played Robert Knox in The Flesh and the Fiends, based on the true story of a doctor who purchased human corpses for research from the serial killer duo Burke and Hare.[3] Cushing had previously stated Knox was one of his role models in developing his portrayal of Baron Frankenstein.[83] The film was called Mania in its American release. Cushing appeared in several films in 1961, including Fury at Smugglers' Bay, an adventure film about pirates scavenging ships off the English coastline;[84] The Hellfire Club, where he played a lawyer helping a young man expose a cult;[85] and The Naked Edge, a British-American thriller about a woman who suspects her husband framed another man for murder. The latter film starred Deborah Kerr, Cushing's old co-star from The End of the Affair, and Gary Cooper, one of Cushing's favorite actors.[84] The Hellfire Club, although not a Hammer Studios film, was written by regular Hammer screenwriter Jimmy Sangster, and featured frequent Hammer star Miles Malleson.[85]

In 1965, Cushing appeared in the Ben Travers farce play Stark at the Westminster's Garrick Theatre. It would be his final stage performance for a decade, but he continued to stay active in film and television during this period.[86] In 1965, he portrayed Dr. Who in two science fiction films by AARU Productions based on the cult British television series, Doctor Who. Although Cushing's protagonist was based on the Doctor from that series, his portrayal of the character was fundamentally different, most especially in the fact that Cushing's Dr. Who was a human, whereas the original Doctor was extraterrestrial. As the films were oriented more toward children than the series was, Cushing's portrayal of the doctor was kinder and more lovable than past incarnations, which was in part an effort on the actor's part to move away from his typical horror persona.[87] Cushing played the role in Dr. Who and the Daleks (1965) and Daleks' Invasion Earth: 2150 A.D. (1966).[3]

Starting in 1965, Cushing starred in the fifteen-episode BBC television series Sherlock Holmes, once again reprising his role as the title character. The episodes ran from 1965 to 1968. Douglas Wilmer had previously played Holmes for the BBC,[8] but he turned down the part in this series due to the extremely demanding filming schedule. Fourteen days of rehearsal was originally scheduled for each episode, but they were cut down to ten days for economic reasons. Many actors turned down the role as a result, but Cushing accepted,[88] and the BBC believed his Hammer Studios persona would bring what they called a sense of "lurking horror and callous savagery" to the series.[8] Production lasted from May to December,[89] and Cushing adopted a strict regimen of training, preparation and exercise.[90] He tried to keep his performance identical to his portrayal of Holmes from The Hound of the Baskervilles.[91] Although the series proved popular, Cushing felt he could not give his best performance under the hectic schedule, and he was not pleased with the final result.[89][92]

A publicity photo of Christopher Lee and Peter Cushing, who frequently co-starred alongside each other and became extremely close friends

Cushing appeared in a handful of horror films by the independent Amicus Productions, including Dr. Terror's House of Horrors (1965), as a man who could see into the future using tarot cards;[93] The Skull (1965), as a professor who became possessed by a spiritual force embodied within a skull;[94] and Torture Garden (1967), as a collector of Edgar Allan Poe relics who is robbed and murdered for an unpublished Poe manuscript.[95] Cushing also appeared in non-Amicus horror films like Island of Terror (1966) and The Blood Beast Terror (1968), in both of which he investigates a series of mysterious murders.[96][97] Cushing considered The Blood Beast Terror the worst film he ever acted in.[98] Also in 1968, he appeared in Corruption, a film that was billed as so horrific that "no woman will be admitted alone" into theaters to see it.[99] In Corruption, Cushing played a surgeon who attempts to restore the beauty of his fiancee (played by Sue Lloyd), whose face is horribly scarred in an accident.[100]

In July 1969, Cushing appeared as the straight man in a sketch comedy show hosted by comedians Morecambe and Wise. In the skit, Cushing portrayed King Arthur, while the other two gave comedic portrayals of characters like Merlin and the knights of the Round Table. Cushing continued to make occasional cameos on the show over the next decade, portraying himself desperately attempting to collect a payment for his previous acting appearance on the show.[101] Cushing and Lee made cameos as their old roles of Dr. Frankenstein and the monster in the 1970 comedy One More Time, which starred Jerry Lewis and Sammy Davis, Jr.[102] The single scene took only one morning of filming, which Cushing agreed to after Davis asked him to do it as a favor.[61] The next year, Cushing appeared in I, Monster (1971),[2] which was adapted from Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and featured Christopher Lee in the title dual role. During this time, Cushing's wife Helen was in extremely poor health and, to ensure he could spend time with her, Cushing began taking a milk-train home rather than risk getting stuck in traffic by driving the long commute.[103] Later that year he was set to appear in Blood from the Mummy's Tomb (1971), an adaptation of the Bram Stoker novel The Jewel of Seven Stars. He was forced to withdraw from the film to care for Helen, and was ultimately replaced by Andrew Keir.[104]

Death of Helen Cushing

- "I knew the only way to combat it was to just work and work and work, so I accepted anything that was offered. People were very good. I'm sure the business really rallied round and made jobs for me."

- ―Peter Cushing, regarding the death of his wife[105]

After long sporadic periods of poor health, Helen Cushing died of emphysema in 1971.[103] Peter Cushing was devastated by the loss, and avoided social engagements and public events for the next eleven years.[39] Some media reports indicated Cushing harbored suicidal thoughts at this time, but his deep religious convictions made such a measure out of the question.[101][106] He staved off his grief by burying himself in his work, appearing in thirty-two films between 1971 and 1982,[39] twelve of which were filmed in the first year after her death.[16] In 1971 he contacted the Royal National Institute for the Blind and offered to provide voice acting for some of their talking books. They immediately accepted, and among the works Cushing recorded was The Return of Sherlock Holmes, a collection of thirteen one-hour stories. The readings proved therapeutic for Cushing during this difficult period.[105] In 1972, Cushing appeared in the horror film Bloodsuckers[107] and starred alongside Vincent Price in Dr. Phibes Rises Again!, a sequel to the previous year's The Abominable Dr. Phibes.[21] Cushing continued to appear in several Amicus Productions films during this period, including Tales from the Crypt (1972), From Beyond the Grave (1973),[9] And Now the Screaming Starts! (1973),[63] and The Beast Must Die (1974).[108]

Peter Cushing helped design the make-up and costume for his resurrected character in Tales from the Crypt (1972).

For Tales from the Crypt, an anthology film made up of several horror segments, Cushing was offered the part of a ruthless businessman who is killed when his wife discovers a Chinese figurine and wishes for a fortune. Cushing did not like the part and turned down the role, which eventually went to Richard Greene. Instead, Cushing asked to play Arthur Grymsdyke,[109] a kind, working-class widower who gets along well with the local children, but falls subject to a smear campaign when his snobbish neighbors falsely accuse him of being a child molester. Eventually the character is driven to commit suicide, but returns from the grave to seek revenge against his tormentors.[110] Not only was Cushing cast in the role, but several changes were made to the script at his suggestion. Originally, all of the character's lines were spoken aloud to himself, but Cushing suggested he speak to a framed photo of his deceased wife instead, and director Freddie Francis agreed.[109] Cushing used the emotions from the recent loss of his wife to add authenticity to the widower character's grieving.[110] Make-up artist Roy Ashton designed the costume and make-up Cushing wore when he rose from the dead,[110] but the actor helped Ashton develop the costume, and donned a pair of false teeth that he previously used in a disguise during the Sherlock Holmes television series.[111] His performance in Tales from the Crypt won him the Best Male Actor award at the 1971 French Convention of Fantasy Cinema in France.[109]

In 1975, Cushing was anxious to return to the stage, where he had not performed in ten years. Around this time he learned that Helen Ryan, an actress who impressed him in a televised play about King Edward VII, was planning to run the Horseshoe Theatre in Basingstoke with her husband, Guy Slater. Cushing wrote to the couple and suggested they stage The Heiress, a play by Ruth and Augustus Goetz, with Cushing himself in the lead role. Ryan and Slater agreed, and Cushing later said performing the part was his most pleasant experience since his wife had died four years earlier.[86] Cushing also starred in several horror films in 1975. Among them were Land of the Minotaur, where he played Baron Corofax, the evil leader of a Satanic cult opposed by a priest played by Donald Pleasence.[112] Another was The Ghoul, where he played a former priest hiding his cannibalistic son in an attic. That film marked the first pairing between Cushing and producer Kevin Francis, who worked in minor jobs at Hammer Studios and long aspired to work with Cushing, whom he admired deeply. The two went on to make two other films together: Legend of the Werewolf (1975) and The Masks of Death (1984).[113] The Ghoul also featured Don Henderson, who later played General Cassio Tagge alongside Cushing in Star Wars.[114] In 1976, Cushing appeared in the television film The Great Houdini as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of the Sherlock Holmes character Cushing had played several times throughout his career.[105][115] Cushing wrote the forewords to two books about the detective: Peter Haining's Sherlock Holmes Scrapbook (1974) and Holmes of the Movies: The Screen Career of Sherlock Holmes (1976), by David Stuart Davies.[116] Cushing also appeared in the 1977 horror film The Uncanny.[117]

Star Wars

- "After we started designing the costumes, and I saw what Darth Vader looked like, I felt I really needed a human villain, too, because you can't see Darth Vader's face. I got a little nervous about it, so I wanted somebody really strong, a really good villain — and actually Peter Cushing was my first choice on that."

- ―George Lucas

Peter Cushing portrayed Grand Moff Wilhuff Tarkin in Star Wars (1977), one of his most widely seen performances.

Film director George Lucas approached Cushing with the hopes of casting the actor in his upcoming space fantasy film, Star Wars. Since the film's primary antagonist Darth Vader wore a mask throughout the entire film and his face was never visible, Lucas felt a strong human villain character was necessary. This led Lucas to write the character of Grand Moff Wilhuff Tarkin, a high-ranking Imperial governor and commander of the planet-destroying battlestation, the Death Star. Lucas felt a talented actor was needed to play the role and said Peter Cushing was his first choice for the part.[118] However, Cushing has claimed that Lucas originally approached him to play the Jedi Master Obi-Wan Kenobi, and only decided to cast him as Tarkin instead after the two met each other. Cushing said he would have preferred to play Kenobi rather than Tarkin,[119][120] but could not have done so because he was to be filming other movie roles when Star Wars was shooting, and Tarkin's scenes took less time to film than those of the larger Kenobi role. Although not a particular fan of science fiction, Cushing accepted the part because he believed his audience would love Star Wars and enjoy seeing him in the role.[119]

Cushing joined the cast in May 1976, and his scenes were filmed at Elstree Studios in Borehamwood.[119] Along with Alec Guinness, who was ultimately cast as Kenobi, Cushing was among the most famous actors at the time to appear in Star Wars, as the rest of the cast was still relatively unknown.[121] As a result, Cushing was paid a larger daily salary than most of his fellow cast, earning £2,000[118]—the equivalent of $3,680 in American dollars[122]—per day compared to weekly salaries of $1,000 for Mark Hamill, $850 for Carrie Fisher and $750 for Harrison Ford, who played protagonists Luke Skywalker, Princess Leia Organa and Han Solo, respectively.[118] When Cushing smoked between shots, he wore a white glove so the make-up artists would not have to deal with nicotine stains on his fingers.[120] Like Guinness, Cushing had difficulty with some of the technical jargon in his dialogue, and claimed he did not understand all of the words he was speaking. Nevertheless, he worked hard to master the lines so they would sound natural and that his character would appear intelligent and confident.[123]

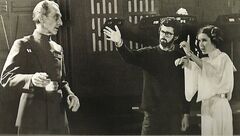

Director George Lucas (middle) instructs Peter Cushing and actress Carrie Fisher on the set of Star Wars.

Cushing got along well with the entire cast, especially his old Hammer Studios co-star David Prowse (who played Darth Vader) and Fisher, who was appearing in her first major role as Princess Leia Organa.[119][120] The scene in which Tarkin and Organa appear together on the Death Star, just before the destruction of the planet Alderaan, was the first scene with major dialogue that Fisher filmed for Star Wars.[123] Cushing consciously attempted to define their characters as opposite representations of good and evil, and the actor purposely stood in the shadows so the light would shine on Fisher's face. Fisher said she liked Cushing so much that it was difficult to act as though she hated Tarkin,[119] and she had to substitute somebody else in her mind to muster the feelings. Although one of her lines referred to Tarkin's "foul stench," she said the actual actor smelled like "linen and lavender," something Cushing attributed to his tendency to wash and brush his teeth thoroughly before filming because of his self-consciousness about bad breath.[123] Upon learning of that line, Cushing asked Lucas, "Do you want me to look as if I have body odor?"[120]

During the filming of Star Wars, Cushing was provided with a pair of boots far too small to accommodate the actor's size twelve feet. This caused a great deal of pain for him during shooting sessions, but the costume designers did not have enough time to get him another pair. As a result, he asked Lucas to film more close-up shots of him from the waist up and, after the director agreed, Cushing wore slippers during the scenes where his feet were not visible.[124][125][126] Some of the actors who appeared in scenes with Cushing had trouble not laughing because of the shoes.[120] During rehearsals, Lucas originally planned for Tarkin and Vader to use a giant screen filled with computerized architectural representations of hallways to monitor the whereabouts of Skywalker, Solo and Organa. Although the idea was ultimately abandoned before filming began, Cushing and Prowse rehearsed those scenes in a set built by computer animation artist Larry Cuba.[127] The close-up shots of Cushing aboard the Death Star, shown right before the battlestation is destroyed, were actually extra footage taken from previously-shot scenes with Cushing that did not make the final film. During production, Lucas decided to add those shots, along with second unit footage of the Death Star gunners preparing to fire, to add more suspense to the film's space battle scenes.[128]

Mark Hamill did not perform in any scenes with Cushing, but Hamill was a fan of the actor and specifically sought him out to share his admiration and ask for an autograph. Hamill asked questions about Cushing's past acting career, and he asked specifically what it was like working with Laurel and Hardy in A Chump at Oxford.[129] Hamill and Cushing had a lunch together on October 9, 1976.[130] When Star Wars was first released in 1977, most preliminary advertisements touted Cushing's Tarkin as the primary antagonist of the film, not Vader;[131][132] in a 1977 Newsweek article, writer Jack Kroll incorrectly stated that Tarkin was the leader of the Empire, and called Vader his "lieutenant."[132] Cushing was extremely pleased with the final film, and he claimed his only disappointment was that Tarkin was killed and could not appear in the subsequent sequels. The film gave Cushing the highest amount of visibility of his entire career, and helped inspire younger audiences to watch his older films.[124][133]

The Tarkin character was not identified by the first name Wilhuff until the release of the LucasArts screensaver and computer media program Star Wars Screen Entertainment in 1994, the year of Cushing's death.[134] Years later, Cushing's friend and frequent co-star Christopher Lee would also be cast as a Star Wars character, portraying Count Dooku in the prequel trilogy films Attack of the Clones (2002) and Revenge of the Sith (2005). In an interview with the magazine Star Wars Insider, Lee claimed the fact that Cushing had previously appeared in Star Wars made the role that much more special to him.[135] Wilhuff Tarkin appeared briefly in Revenge of the Sith, during a scene near the end of the film as Darth Vader and the Galactic Emperor Palpatine stare at the still under-construction Death Star. Animation director Rob Coleman said the filmmakers considered creating a digital version of Peter Cushing for the scene, and discussed the idea at length with Lee because the two were such close friends.[136] They also considered using unused footage of Cushing from Star Wars and digitally animating Cushing's lips to match new dialogue.[137] However, they ultimately decided to cast actor Wayne Pygram, who was fitted with prosthetic makeup that made him very closely resemble Cushing.[136] Starting in 2011, the Tarkin character also started appearing in the Cartoon Network animated television series Star Wars: The Clone Wars. The character was designed by sculptor Darren Marshall, who based him on Cushing's image. Marshall said he grew up with the Hammer films, and admired the talents and expressive faces of both Cushing and Lee.[138] Stephen Stanton, the voice actor who portrayed Tarkin in the show, said he researched Cushing's performances in the Hammer films, then tried to imitate what Cushing might have sounded like in his mid-thirties and softened it to give a level of humanity to Tarkin.[139]

Later career and death

- "All I am is a bit tired now, and unfortunately I can't work as much as I would like to. But I would so dearly love to be playing in the next Sherlock Holmes picture."

- ―Peter Cushing

Toward the end of his career, after Star Wars, Cushing performed in films and roles critics widely considered below his talent.[124] Director John Carpenter approached him to appear in the horror film Halloween (1978) as Samuel Loomis, the psychiatrist of murderer Michael Myers, but Cushing turned down the role. It eventually went to Donald Pleasence, Cushing's former co-star from Nineteen Eighty-Four and Land of the Minotaur.[140] Cushing made a cameo appearance as himself in a 1980 Christmas special hosted by the comedians Morecambe and Wise. In the skit, Cushing complained that he had not been paid for the skit he appeared in during Morecambe and Wise's show in 1969.[101] In 1983, Cushing appeared alongside his old co-stars Christopher Lee and Vincent Price in House of the Long Shadows, a horror-parody film featuring Desi Arnaz, Jr. as an author trying to write a Wuthering Heights-like novel in a deserted Welsh mansion.[7]

In 1984, Cushing appeared in the television film The Masks of Death, marking both the last time he would play detective Sherlock Holmes and the final performance for which he received billing.[124] He appeared alongside actor John Mills as Watson, and the two were noted by critics for their strong chemistry and camaraderie. As both actors were in their seventies, screenwriter N.J. Crisp and executive producer Kevin Francis both in turn sought to portray them as two old-fashioned men in a rapidly changing world. Cushing biographer Tony Earnshaw said Cushing's performance in The Masks of Death was arguably the actor's best interpretation of the role, calling it "the culmination of a life-time as a Holmes fan, and more than a quarter of a century of preparation to play the most complex of characters".[141] The final notable roles of Cushing's career were the 1984 comedy Top Secret!, the 1984 fantasy film Sword of the Valiant and the 1986 adventure film Biggles: Adventures in Time.[124] In 1986, he appeared on the British television show Jim'll Fix It, in which host Jimmy Savile would arrange for the wishes of guests to be granted. Cushing wished for a strain of rose to be named after his wife, and Savile arranged for the "Helen Cushing Rose" to be grown at the Wheatcroft Rose Garden in Edwalton, Nottinghamshire.[125]

Peter Cushing in 1986, at age 72

During this period, Cushing was honored by the British Film Institute, which invited him in 1986 to give a lecture at the National Film Theatre. He also staged An Evening with Peter Cushing at St. Edmund's Public School in Canterbury to raise money for the local Cancer Care Unit. In 1987, a watercolor painting Cushing painted was accepted by Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex and auctioned at a charity event he organized to raise funds for The Duke of Edinburgh's Award Scheme.[142] Also that year, a sketch Cushing drew of Sherlock Holmes was accepted as the official logo of the Northern Musgraves Sherlock Holmes Society.[143]

Cushing wrote two autobiographies, Peter Cushing: An Autobiography (1986) and Past Forgetting: Memoirs of the Hammer Years (1988).[3] Cushing wrote the books as what he called "a form of therapy to stop me going stark, raving mad" following the loss of his wife. His old friend and co-star John Mills encouraged him to publish his memoirs as a way of overcoming the reclusive state Cushing had placed himself into following her death.[133] In 1989, Queen Elizabeth II named him to the Order of the British Empire for his contributions to the British film industry.[144] Cushing also wrote a children's book called The Bois Saga, a story based on the history of England. Published in 1994, it was originally written specifically for the daughter of Cushing's long-time secretary and friend Joyce Broughton, to help her overcome reading problems resulting from her dyslexia. It was Broughton who encouraged Cushing to have the book published.[145] His final acting job was narrating, along with Christopher Lee, the Hammer Films documentary Flesh and Blood: The Hammer Heritage of Horror (1994), which was recorded only a few weeks before Cushing's death.[6] Lee recognized Cushing's health was fading and did his best to keep his friend's spirits up, but Lee later claimed he had a premonition that it would be the last time he ever saw Cushing alive, which proved to be true.[71]